THE SAHARA — It was the last difficult stage of one of the world’s most punishing races. The runners, by now walking, began a steep climb up a 25 percent grade, which required many of them to use fixed ropes to reach the summit.

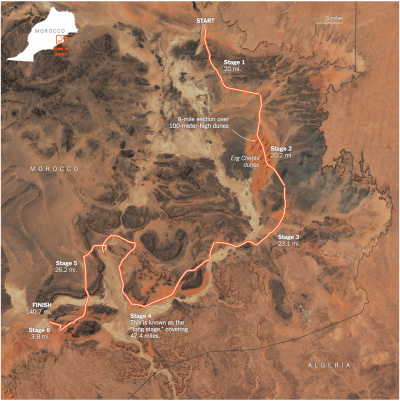

As Amy Palmiero-Winters, 46, of Hicksville, N.Y., began the sharp ascent, her prosthetic left leg became stuck beneath a rocky outcropping. Each time she tried to lift the carbon fiber leg, her shoe bounced against the rock, unable to clear it. Finally, the runner behind her reached and pulled the leg backward, and Palmiero-Winters swung her foot over the impediment. She was free to continue her attempt to become the first female amputee to complete the Marathon des Sables, a stage race roughly equivalent to running 23.5 miles a day for six days in relentless heat over sand dunes, rocks, dry valleys, stony plateaus and salt flats in southern Morocco.

About 780 runners (and one dog) from 51 nations fell into single file to make the abrupt ascent: A woman from Malaysia who ran the entire 140.7 miles of the ultramarathon in flip-flops; the dog, a nomad nicknamed Cactus, who ran in five of the stages and went viral on the internet; a jeweler from Dubai who once worked the American South, eating furtive meals at Waffle House counters with diamonds strapped to his chest.

Each runner carried in a backpack everything needed for a week in the desert: food, sleeping bag, compass, headlamp, venom pump to minimize any bites from snakes and scorpions. Each had his or her own motivation: to reconsider a bad marriage; to kick a habit of sloth and cigarettes; to plot a new career after the military; to find a new challenge after rowing across the Arctic Ocean.

This was the first attempt at the Marathon des Sables for Palmiero-Winters or any female amputee in the 34 years of the race, organizers said. Her lower left leg was amputated below the knee in 1997 after a motorcycle accident. She is a single mother of two teenagers, 15 and 13, intensely driven, remarkably persevering. She trained for the heat of the desert, in part, by doing lunges and burpees in a sauna. She also placed her fiancé’s two young boys on her shoulders while she ran during her CrossFit workouts, then put them on her back while she did bear crawls, to grow accustomed to the heaviness of a backpack.

Before this desert race, she had established a dozen or so world records or firsts for below-the-knee amputees, including running the 26.2 miles of the 2006 Chicago Marathon in 3 hours 4 minutes 16 seconds. In 2009, she was named the winner of the A.A.U. James E. Sullivan Award as the nation’s top amateur athlete. In 2011, she became the first female amputee to finish the Badwater Ultramarathon, a brutal 135-mile race in July from Death Valley to the Mount Whitney trailhead at 8,300 feet.

Last summer, Palmiero-Winters was one of only 12 finishers at the hellish Spartan Death Race in Pittsfield, Vt., a 72-hour slog that included running, hiking and extreme tasks like 3,000 burpees, a 12-hour crawl under barbed wire and a seven-hour rope climb.

“Amy is the toughest person I know,” said Joe De Sena, the founder of the Death Race.

Now she faced perhaps her harshest test, this marathon of the sand, taking tens of thousands of jarring strides on her prosthetic leg, her natural leg having borne years of asymmetrical pounding, the calf with reduced function, the foot with broken metal screws, the second toe fused straight.

She wanted to complete this race to inspire, to show how not to succumb to artificial limits, she said. She wanted her children to understand about pushing the envelope and not selling themselves short.

“When it’s your last day, you want to come in skidding sideways, your body worn out,” she said, discussing her approach not only to running but to life.

Palmiero-Winters did not spend much time studying the Marathon des Sables course. She did not want to know about terrain changes. She wore a watch, not to measure her pace or heart rate, but to remember what time it was back home on Long Island. Her approach was not to think, only to put her head down and run. But that was a risky strategy in the desert.

At 5 feet 7 inches and 120 pounds, she faced enormous challenges almost immediately and repeatedly — first with her breathing, then with running on a carbon fiber leg in a forbidding environment while carrying a backpack that weighed 19 pounds. Her 13-year-old daughter, Madilynn, had seemed to acutely understand the risks. She gave her mother a note that was laminated and hung from the rucksack: “Good luck. I love you. Don’t die.”

At 5 feet 7 inches and 120 pounds, she faced enormous challenges almost immediately and repeatedly — first with her breathing, then with running on a carbon fiber leg in a forbidding environment while carrying a backpack that weighed 19 pounds. Her 13-year-old daughter, Madilynn, had seemed to acutely understand the risks. She gave her mother a note that was laminated and hung from the rucksack: “Good luck. I love you. Don’t die.”

Growing up in Meadville, Pa., east of Cleveland and near Lake Erie, Palmiero-Winters found a freedom in running. She ran track and cross-country in high school. Sometimes she ran from her family’s drive-in to deliver orders of chicken wings to softball tournaments. Other times, she headed out to run after the drive-in closed at night, a family friend trailing in a Ford Ranger.

“Some people are born to do certain things,” said the family friend, Stacy Meyer. “She was born to run, I guess.”

Running, too, became a form of escape, Palmiero-Winters said, when she was raped in high school and when her father drank and physically and verbally abused her mother or when her own brief marriage turned turbulent. Both of her parents died this year.

“Sports gave me self-confidence,” she said. “When something bad happened to me, I went out for a run. It kept me from any darkness.”

She attended Youngstown State in Ohio for a time, and planned to study criminal justice, join the military and become a police officer. But she said she dropped out of school when her family could no longer afford the cost. She became a carbide furnace operator at a plant in Meadville. Later, she became a welder.

Her life’s trajectory changed on April 14, 1994, as she rode her Harley-Davidson 883 Sportster with friends. As Palmiero-Winters came up a hill in Meadville, a woman pulled from a stop sign and struck her, badly injuring her lower left leg. Doctors wanted to amputate immediately, she said, but she resisted. She was a runner. She could not imagine not running.

In 1995, she ran the Columbus Marathon in Ohio in 4:03:37 but felt pain in every step. She realized that a door was beginning to close. She was only putting off the inevitable. By then, she said, atrophy and surgery had reduced the size of her left foot to 4½ from 7½. Her left ankle also began to fuse. Finally, after more than two dozen surgeries, her left leg was amputated below the knee on July 27, 1997.

Palmiero-Winters tried to run again when she received a prosthesis, but it was not built for sports. If she ran three miles, she needed three days to recover. At one point, she threw out all of her running gear. That was it, she thought. Then she reconsidered. Running defined her. In October 2005, with a somewhat better prosthetic, she won her division of athletes with disabilities at the world triathlon championships in Hawaii. She wanted to begin running races of 100 miles or more, but her running leg was low-tech, its foot made of wood and foam.

A fellow competitor told her about A Step Ahead Prosthetics in Hicksville, and she drove there from Meadville with her mother and her two children. Erik Schaffer, the company’s founder and chief executive, called the prosthetic leg that Palmiero-Winters arrived with “the meat grinder,” which left her with bruising and contusions on her residual leg and was effectively like trying to run in a ski boot.

He began to make custom running legs for her, and in 2010, Palmiero-Winters became the first amputee to be named to a United States national track team in a championship event. She competed in the 24-Hour World Championships, helping the Americans finish fourth.

“Amy is kind of like a mudder,” Schaffer said. “The worse the conditions, the better the Amy.”

She is now the company’s director of operations. Palmiero-Winters took three to five prosthetic legs with her to many ultra races to adapt to variable terrain and was sometimes aided by a crew from A Step Ahead. But support crews are not allowed at the Marathon des Sables, and she brought only one extra prosthesis for walking when she was not racing.

On the bottom of her running blade in the Sahara, Palmiero-Winters wore a scrap of Goodyear tire, three and a half inches wide, for traction. The prosthesis included an air chamber to cool its outer and inner layers. Then the leg was coated in a chalky color with paint used on the roofs of houses and buildings in the desert.

THE RACE…

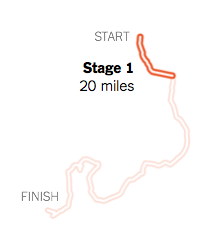

STAGE ONE.

The Marathon des Sables began on April 7, the morning still cool, hills pink and brown on the horizon, the sand and rock the tawny color of lions. With loudspeakers blasting AC/DC’s “Highway to Hell,” Palmiero-Winters and the rest of the field took off for a 20-mile stage. She wore what most wore for shade, a hat with flaps over the ears and neck, which gave the runners the look of extremely fit beagles.

The Marathon des Sables began on April 7, the morning still cool, hills pink and brown on the horizon, the sand and rock the tawny color of lions. With loudspeakers blasting AC/DC’s “Highway to Hell,” Palmiero-Winters and the rest of the field took off for a 20-mile stage. She wore what most wore for shade, a hat with flaps over the ears and neck, which gave the runners the look of extremely fit beagles.

Palmiero-Winters stuck a dental floss pick into the liner of her prosthetic leg to keep the nuts and fruit and seeds from her protein bars from getting stuck in her teeth. She also slipped an MP3 player inside the liner. She planned to listen to Eminem for the entire race, drawn to the rapper’s me-against-the-world bravado.

“Nobody believed in him; he paved his own path,” Palmiero-Winters said. “Same with me.”

Her first choice was a Dr. Dre song featuring Eminem called, “I Need a Doctor.” It was not meant to be a literal request. But only about five and a half miles into the race, as Palmiero-Winters crested a short, steep hill, her lips appeared to bulge, as if with a plug of tobacco. She feared she was going into anaphylactic shock from an unknown allergy. Her tongue seemed thick, her words heavy.

“It’s shutting down my airway,” she said. “My throat is closing.”

STAGE TWO.

She had an epinephrine injector to treat the attack, but hesitated to use it. The Marathon des Sables allows only limited assistance to runners. Palmiero-Winters feared that if she used the EpiPen now and her shortness of breath returned during another stage, she might be forced to leave the race.

She had an epinephrine injector to treat the attack, but hesitated to use it. The Marathon des Sables allows only limited assistance to runners. Palmiero-Winters feared that if she used the EpiPen now and her shortness of breath returned during another stage, she might be forced to leave the race.

Fortunately for her, her airways soon opened without an injection and her breathing problem did not return.

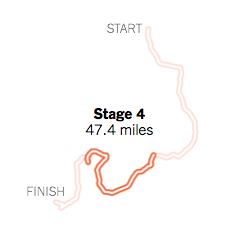

The next day featured a 20.2-mile stage, including perhaps the most difficult section of the race — eight miles traversing some of the biggest dunes in Morocco, known as the Erg Chebbi. The unremitting ups and downs were the cumulative equivalent of climbing a 115-story building.

The sun was relentless. The wind picked up and sand blew into eyes and noses. Some runners sought relief from the heat under bushes in the dunes. A former British paratrooper crawled over some dunes to navigate the loose sand. A Frenchwoman fell out, exhausted, as she cleared the dune field.

Palmiero-Winters had hoped to run the entire race. But that was impossible in this terrain. So she improvised and switched from her running prosthetic to her walking prosthetic. The running leg, a blade, kept her on her tiptoes; the walking leg was attached to a running shoe and had a heel. It would give her more surface area to plant into the sand and, she hoped, a shallower step. But even before the dunes, sand began to pour into the running shoe and the prosthetic foot.

She had no sand gaiter for that prosthetic and tried, futilely, to cover the opening between the carbon fiber leg and the shoe with a plastic bag. As the dunes approached, she grew discouraged.

“I feel like such a failure,” she said.

All runners feel emotional swings during long races. And while Palmiero-Winters struggled in the dunes, she also drew strength by considering her life’s impediments and how she had overcome them.

Through the dune stage, she used trekking poles and followed another runner who veered from the well-trod path, seeking spots of untrammeled, crusty sand. This more secure footing required less energy to plant and withdraw her shoe. She also looked for tracks where passing camels had made only slight indentions.

After nearly three hours, Palmiero-Winters emerged from the dunes and consoled a British woman who was on her back with blistered feet. “I want to cry, too,” Palmiero-Winters said, “but you’ve got this, kiddo. Take deep breaths, one foot in front of the other.”

At the finish line, she returned to the tent she shared nightly with six other runners and did 100 push-ups.

STAGE THREE.

For the third stage, a 23.1-miler, Palmiero-Winters started with the running blade but found it impossible to lengthen her stride in the sand and on rocky plateaus. Her body was taking a tremendous pounding. A prosthesis cannot soften the landing on different surfaces the way a natural leg can by flexing at the knee and ankle to maintain a certain amount of “give” as the foot strikes the ground.

For the third stage, a 23.1-miler, Palmiero-Winters started with the running blade but found it impossible to lengthen her stride in the sand and on rocky plateaus. Her body was taking a tremendous pounding. A prosthesis cannot soften the landing on different surfaces the way a natural leg can by flexing at the knee and ankle to maintain a certain amount of “give” as the foot strikes the ground.

With each choppy stride, the weight of Palmiero-Winters’s backpack jolted the back and side of her left knee. Skin began to peel inside the liner of her prosthesis. Three toenails on her right foot began to loosen. The sun was ruthless and the thermometer on her prosthetic leg reached 122 degrees. A former United States Marine, an amputee who had completed the 2018 Marathon des Sables, had to withdraw as his residual leg began to swell uncomfortably.

Palmiero-Winters told herself, “I don’t know if I can do this.”

When she removed the prosthesis after the stage, one of her tent mates asked, “Is that iodine?”

“No,” Palmiero-Winters said. “That’s blood.”

She went to the medical tent and returned with disinfectant and a bandage. It was clear that her residual leg would hurt with each stride the rest of the way. So she would keep taking one step, then the next, and repeating to herself a line from Dory in “Finding Nemo”: “Just keep swimming.”